Recovery to Resilience

Extension Helps Shape Western NC’s Future After Helene

A hawk catches an updraft and soars over the lush green trees. An oriole flits from branch to branch along the banks of the stream, while a black vulture circles high above.

Closer to the ground, a different type of flyer moves through the air over River Oak Farm, a beef cattle operation in Yancey County. Rather than wings, it has four sets of rotating blades. Instead of looking for food, it is feeding the ground.

The agricultural drone is seeding Red River crabgrass, an annual crop that will become forage and hay for Roger Young’s cows. David Davis, director of the N.C. Cooperative Extension center in Yancey County, is at the controls.

“We’re going to have a hay shortage,” Davis says. “This is a way to get our farmers some hay without having to wait for the perennial crops to recover.”

The hay shortage was caused by Hurricane Helene, the monster storm that devastated the Appalachian Mountain counties of North Carolina in late September 2024, flooding fields and ruining crops.

The drone-seeding program will help Young stay in business by providing feed for about 80 head of cattle.

“This was a fescue field that was covered in sand and debris,” Young says. “I took a dozer and pushed it out, and then I asked David, ‘What should I do?’ We put annual rye in, and the next phase is drone seeding it with crabgrass. In the fall, we’ll do fescue to reclaim the field. I’m very, very pleased with what David suggested. The forage mass is amazing.”

It is one of many ways Extension experts like Davis are helping communities recover and move forward with cutting-edge programs and dynamic solutions to the worst storm anyone in the mountains has ever endured.

A 10,000-Year Storm

Hurricane Helene caused unprecedented destruction. The quiet creeks that dot the landscape became raging rivers, triggering catastrophic flooding. Intense winds toppled trees and power lines. Roads were destroyed. Communication was down.

“It was apocalyptic,” says Michelle South, Extension livestock agent in Avery County. “That’s the only way to describe it.”

People talk about natural disasters in terms of years — a hundred-year storm, a thousand-year flood. Helene was worse.

“There’s a tree in Yancey County marked with floods through the years,” says Jerry Moody, director of the N.C. Cooperative Extension center in Avery County. “Helene was several feet above any of them. This was a 10,000-year flood.”

There were shortages of food, water and medicine, and no good way to get supplies in. The scope of the disaster seemed overwhelming.

“Everybody has their own horror story,” South says. “Every single one of us.”

Emergency Response

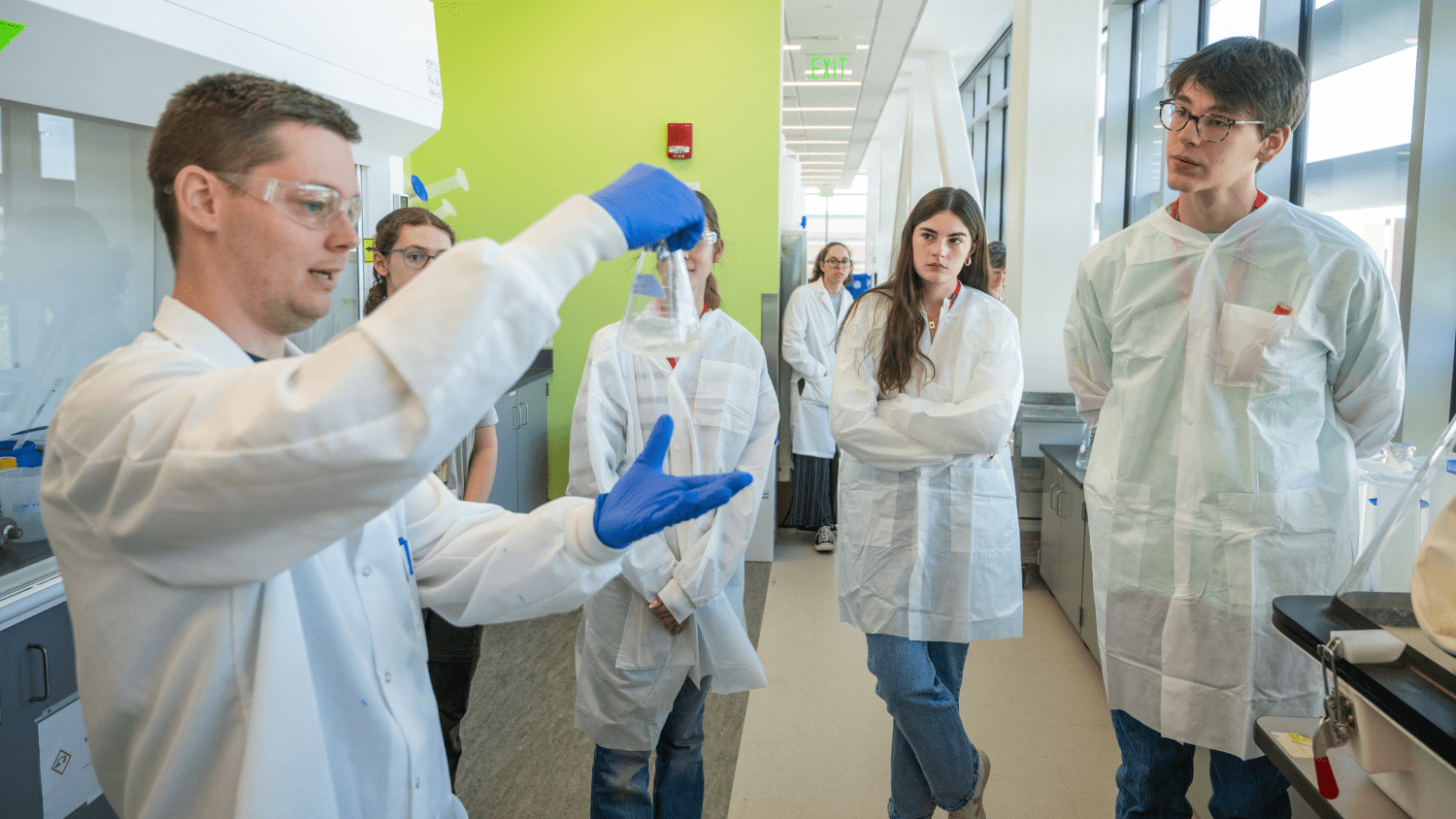

N.C. Cooperative Extension is a trusted network of experts from NC State and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State universities. With 101 centers across North Carolina, Extension agents deliver research-based information and guidance in agriculture, youth development, food and nutrition, natural resources, lawns and gardens, community development and more.

“We’re public servants first and foremost,” says Kendra Phipps, Extension livestock and field crops agent in Watauga County. “We enter this job knowing that’s our role, to give everything we have to our community.”

In the days and weeks after Helene, Extension agents staffed emergency operations centers; set up sites that distributed water, food and medicine; helped coordinate airdrops of vital supplies; and worked with partners to organize donations and distribution of hay, feed, fencing and other livestock supplies.

“Job descriptions got set aside,” says Jim Hamilton, director of the N.C. Cooperative Extension center in Watauga County. “We knew what needed to be done and went full bore into it.”

Extension personnel from across the state joined local agents in responding to immediate needs. Agents from coastal counties, seasoned in disaster response and management, shared their expertise. Others collected relief supplies to send to the mountains.

“Agents in the east really showed up for our agents in the west,” says Stephanie Ward, NC State Extension dairy specialist and associate professor in the Department of Animal Science.

Ward, a native of Haywood County, and her husband, Jason Ward, an NC State Extension specialist in biological and agricultural engineering, delivered Starlink receivers and a generator. With the help of the CALS IT team, the receivers were set up at the Mountain Horticultural Crops Research and Extension Center in Henderson County.

“Once we had communication, we were able to coordinate with NCDA [the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services] to get donated supplies to their response teams,” Ward says.

Agricultural Aid

As food, water and household items reached the region, Extension agents and specialists pivoted to helping with agricultural needs — setting up distribution sites across the region where farmers could receive hay, fencing and other desperately needed supplies. Donations came in from across the country.

“That was the place Extension could step in and help,” says Ward, who coordinated efforts to manage donations. “We put together an online portal for people to submit what they had to donate. We had a team of agents working to get the donations to distribution centers.”

Sheila Greene, owner of North Fork Farm in the northwest part of Watauga County, was among those who received hay and fencing supplies.

“I literally don’t know what we would have done without [Extension] and the people donating,” she says. “It helped out tremendously.”

Helping with Recovery

Niki Maness noticed that many of the Helene victims in the disaster recovery center in Yancey County seemed dazed and disoriented. After having their lives upended by the storm, they now had to navigate the often confusing bureaucracy for insurance and recovery assistance.

Maness, an Extension Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) agent, worked at the center alongside FEMA personnel to help with paperwork and grant applications. When people saw that she was from the county Extension office and heard her local accent, faces brightened. Here was someone who knew what they had gone through.

“People would see Extension, and they knew that we’re from the county,” she says. “They would come talk to me, and then I would help connect them with resources.”

Every Extension team was involved in the recovery. FCS agents gave advice on food safety. 4-H agents provided a safe and engaging atmosphere for young people who had experienced the traumatic storm. Agriculture and horticulture experts provided immediate assistance to farmers and growers.

Sam Marshall, area specialized agent for ornamentals, procured irrigation equipment to channel water back into rivers and streams and coordinated Extension experts from the central and eastern parts of the state to clean storm debris. His efforts helped salvage crops and support western North Carolina’s $150 million ornamentals industry.

Moody, director of the Extension center in Avery County, partnered with the North Carolina Department of Transportation to figure out how to move 1,000 tractor-trailer loads of Christmas trees out of an area where storm damage had decimated the infrastructure. The effort helped protect the county’s vital $45 million industry.

Soil health was another major concern. Floods stripped away topsoil in some fields, replacing it with rocks. In others, floodwaters deposited layers of sand and silt, potentially introducing pathogens. A team of researchers from CALS’ Department of Crop and Soil Sciences visited western North Carolina to assess soil conditions, test for contaminants and evaluate agricultural risks.

The North Carolina Agromedicine Institute, a collaboration of East Carolina, NC State and N.C. A&T State universities, provided counselors for those traumatized by the storm, particularly producers facing a difficult recovery.

“A therapist comes to our office once a week. I direct her to my growers that I think are at risk.”

“A therapist comes to our office once a week,” Moody says. “I direct her to my growers that I think are at risk.”

A Season of Renewal

Finding solutions to problems is in Extension’s DNA. But helping people rebound after Helene has forced some out-of-the-box thinking.

“I never thought I’d be flying a drone. I never thought I’d be coordinating river cleanup and replanting,” says Davis, the Extension director in Yancey County. “These aren’t our normal programs. And now it’s fairly normal.”

For Jordan English, Extension 4-H agent in Buncombe County, the new normal includes incorporating mental health activities in her work with youth.

“This generation has faced a significant amount of learning loss over the past several years. From the COVID-19 pandemic to missing one month of school due to Helene, these youth have faced multiple traumas,” she says. “Kids are resilient, but those traumas are still serious. 4-H has several curriculums and programs that provide lessons on stress management and helping promote emotional well-being.”

“I never thought I’d be flying a drone. I never thought I’d be coordinating river cleanup and replanting.”

Maness used a grant from the National Extension Association of Family & Consumer Sciences to purchase a mobile kitchen that will enable her to do classes at community gardens and other sites. Some of the classes will focus on preparing meals with foods that have a long shelf life.

“I’ve been focusing on one-pot or no-bake recipes that can be used with canned tuna and rice and how to add more protein and seasonings to change them up a little bit,” she says.

Canning is also a popular topic in an area where power was out for days and weeks.

“I’ve had more classes or questions about canning than I did the entirety of last year,” she says. “People want to learn how to preserve their food.”

Laura Lauffer is an Extension associate with the EmPOWERing Mountain Food Systems program, which works with agribusiness development in 12 western counties. She and her team have focused on providing grants to keep struggling farmers afloat and help others navigate the complex maze of government relief.

“We are working with one of many partner organizations to coach farmers and help them through all this paperwork,” she says.

Moving Forward

Jerry Moody points to a field owned by an ornamental grower in Avery County. Trees are still bent over from the floodwaters.

“Those trees are dead; they just don’t know it yet,” he says.

Farther down the road is a 25-acre field strewn with boulders and rocks deposited by floodwaters. It used to be a hayfield. Now it’s unusable.

“We lost about half of the hayfields in the county,” says South, the Extension livestock agent in Avery County. “About a quarter of them aren’t coming back. There’s no topsoil, no organic matter.”

The storm was a life-changing event. Jennifer Badger, area specialized agent for agribusiness and a 10th-generation resident of Transylvania County, has had many difficult conversations with producers whose livelihoods are in peril.

“I’ve talked with people who are doing a lot of soul searching and trying to figure out if they can even afford to continue to farm because the river dumped so much silt and rock,” she says. “My job is helping people look at their business objectively. And it’s really hard. How do you tell someone who is a multigenerational farmer that it’s not economical for them to do it anymore? How do you tell someone that?”

“How do you tell someone who is a multigenerational farmer that it’s not economical for them to do it anymore? How do you tell someone that?”

Months since Helene hit, producers and Extension agents are still coming to grips with the extent of the damage.

“I don’t believe there’s a recovery,” Moody says. “I believe there’s only a restart, because we will never be Sept. 24, 2024 [the day before Helene], ever again.”

It’s a daunting task, but Extension experts will be there to help.

“We’re going to do anything and everything that we can to help them,” Badger says. “We’ve got grant programs and workshops on how to rebuild and how to look at doing something different.”

Different could mean helping producers find new streams of income. Or different could mean encouraging growers to modernize long-standing practices.

“Most of these pastures were established 60, 70, 80 years ago or longer,” says Matt Poore, NC State Extension specialist in ruminant nutrition. “There have been improvements in genetics and plants in that time. In many cases, it will allow them to upgrade what they grow, what they plant, and how they think about it. That’s a very positive thing going into the future.”

Young, the owner of the field David Davis is seeding with his drone, is one producer who is eager to learn.

“The disaster has caused me to look at different things.”

“The disaster has caused me to look at different things,” he says. “Most of us up here farm the way our grandfathers did. And that wasn’t necessarily the best way. I’m trying to run the farm using the best practices. David has been very helpful in making suggestions.”

Glimmers of Hope

Erin Silver, a 4-H agent in Mitchell County, represented Extension at many emergency briefings after Helene. She was out in the community, helping organize and distribute supplies. She was able to tell new audiences about her youth programs. Her 4-H clubs have grown since the storm, and she secured a sponsor for a livestock program.

“We have a higher number of participants now than we did last year at this point,” she says. “It’s definitely growing.”

Amy Fiedler, owner of Springhouse Farm in Watauga County, was heartbroken when floodwaters destroyed her roadside farm stand. A grant from EmPOWERing Mountain Food Systems helped her rebuild in an area of the county far from a grocery store.

“Our produce stand has always been based on the honor system,” she says. “We stock it, and people get what they need. It has an impact in the way that it fosters community.”

The recovery will be long and hard. But Extension will be there every step of the way — sowing new seeds, rebuilding what was washed away, and helping western North Carolina communities and farms take flight again.

- Categories: