If you want a sweetpotato, you’ve come to the right place. North Carolina is top in the nation for growing the healthy root vegetable. Poultry and eggs? Yep, we’re No. 1 in those, too. The state’s agricultural producers come in at No. 2 for turkeys, trout and Christmas trees, and No. 3 for cucumbers and hogs and pigs. And we’re in the top 10 in apples and blueberries.

But raspberries? Forget about it. The flavorful little red berries don’t grow well here.

“You can’t grow raspberries in North Carolina of any commercial consequence,” according to Cal Lewis. “You can do home gardening and some small-scale things in the mountains, but our summers are way too hot for raspberries.”

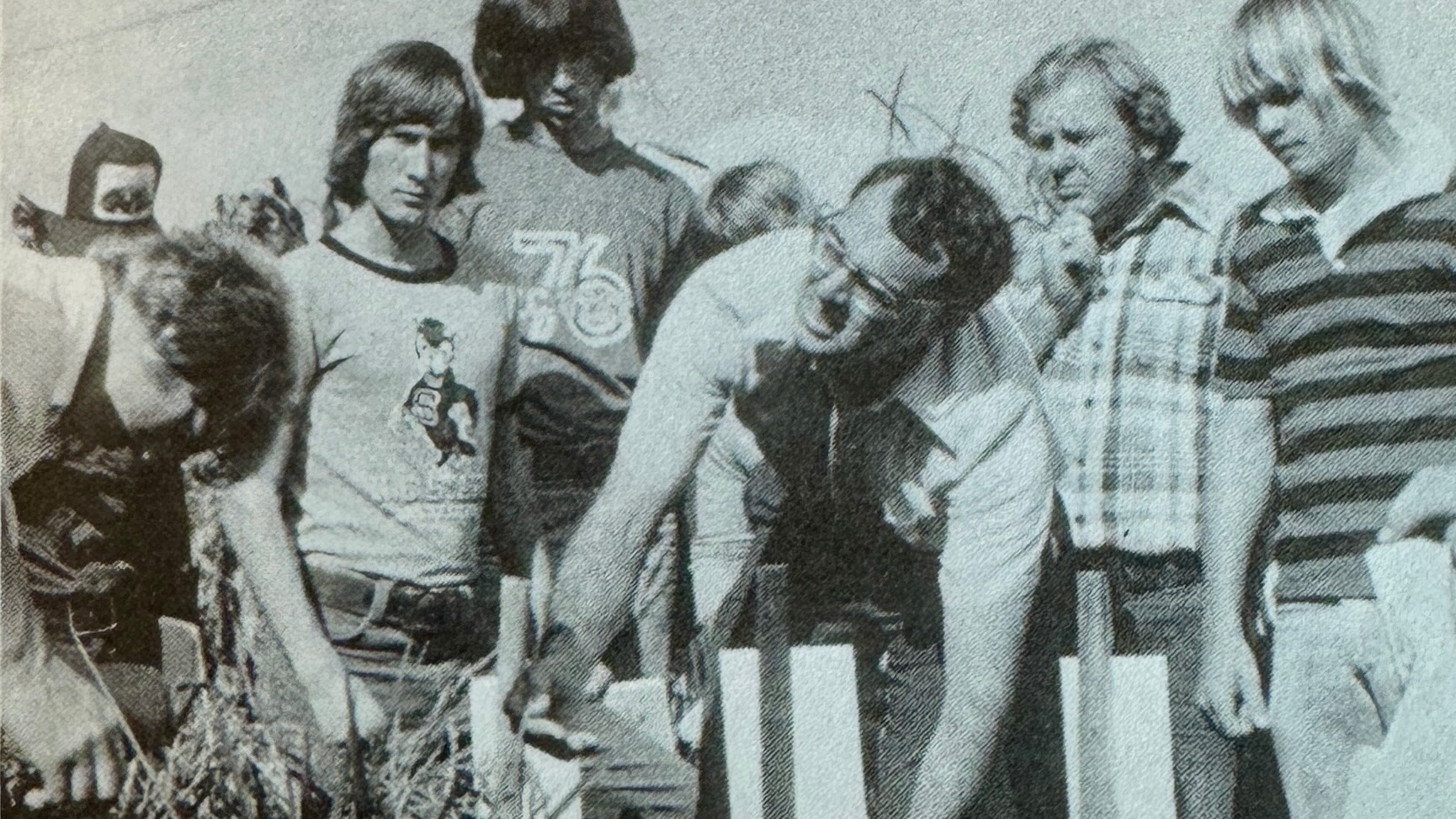

Lewis, a 1977 horticultural science graduate of NC State University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences — and recipient of the college’s Distinguished Alumni award in 2017 — is one of the top berry growers in the state. He owns and operates Lewis Nursery and Farms, a third-generation family farm located in Rocky Point in Pender County, about 18 miles north of Wilmington. His strawberries, blueberries and blackberries can be found in produce aisles across the state and region.

What he says about raspberries is true, especially in the coastal Southeast. They thrive in the cool climates of California and Washington; heat and humidity are not their friends.

Or at least, that used to be true. In conjunction with NC State researchers and Extension specialists, Lewis is now producing a successful crop on the Carolina coast.

“I now joke with people this time of year,” Lewis says. “I ask them, ‘Where in this hemisphere can you get raspberries?’ Anybody that knows anything about raspberries, they’ll say Mexico and California. And I’ll say, ‘Rocky Point, North Carolina.’”

Lewis regarded the conventional wisdom about not being able to grow raspberries in North Carolina not so much as a statement of fact but almost as a dare.

“About three or four years ago, we started having an interest in producing raspberries,” he says. “I love raspberries, number one. And I also wanted to fulfill that fourth berry category here in North Carolina.”

Like his father and grandfather before him, Lewis thrives on innovation. Lewis Farms was a pioneer in the plasticulture method of growing strawberries in North Carolina, which helped revive the industry in the state. He began growing the berries in high tunnels in the winter, giving him a crop in the off season. He saw an opportunity for agritourism, and his retail market on Gordon Road in New Hanover County is always busy with local families and tourists picking their own berries and enjoying some tasty ice cream.

Through his association with Driscoll’s, a California-based company that sources berries globally, Lewis learned of a method of growing raspberries called long cane. He found out that raspberry primocanes grown in containers in a cooler climate can be transported to a warmer area and potentially produce a good harvest.

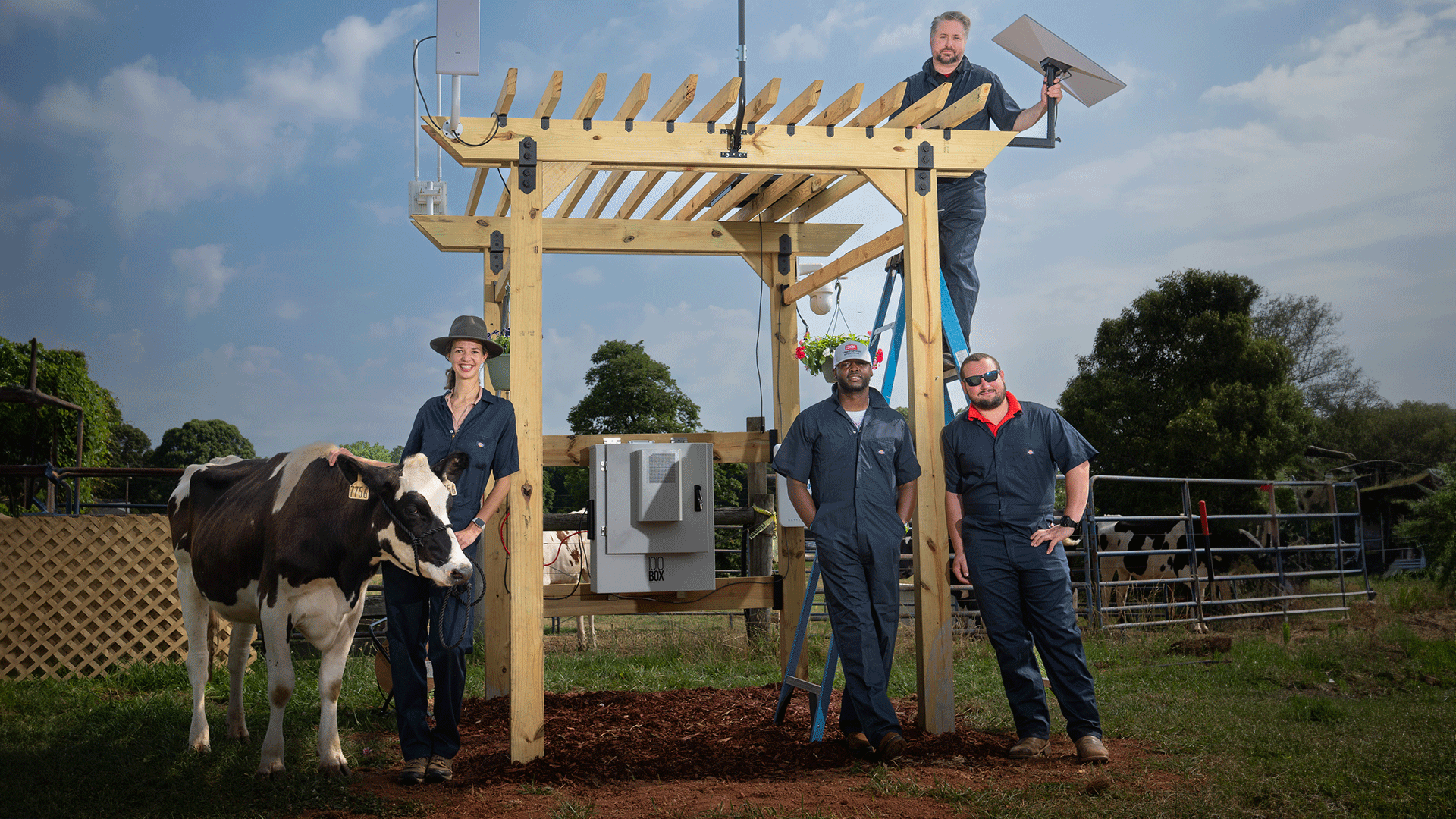

He approached NC State Extension small fruits specialist Gina Fernandez and suggested a collaboration to conduct on-farm trials. Fernandez also knew of the long-cane method, and was eager to try it in North Carolina.

“He donated land, plants and labor for the work at his farm. His goal was to have Extension help develop the system for long-cane raspberries for the state’s growers.”

– Gina Fernandez

“It’s something that in a large part he initiated and funded,” Fernandez says. “He donated land, plants and labor for the work at his farm. His goal was to have Extension help develop the system for long-cane raspberries for the state’s growers.”

Lisa Rayburn, an Extension area agent for commercial horticulture and Fernandez’s graduate student, worked with Lewis to establish the first crop. She remains a frequent visitor to the farm.

“The long-cane production system has been widely adopted in Europe and we wanted to see if it was viable here,” Rayburn says.

In a long-cane system, the raspberry plants are grown for the first year in a nursery in a cool climate. The plants are shipped to the grower in the winter to be set out in pots in high tunnels. The plants are harvested in the spring before the heat of summer has a negative impact on berry size and quality.

“We put them out in our enclosed protective tunnels in January,” says Lewis, who sources his plants from Quebec, Canada. “We harvest fruit in April and May, and we discard the plants after that. Traditionally, raspberries are grown as a perennial crop. In the Northwest and California, they grow in the soil for several years. This is an alternative way that allows us to have raspberries here in North Carolina.”

It required a significant investment in time and money. He had to purchase the plants and construct the high tunnels, which need a ventilation system to ensure the raspberries are warm in the winter and cool in the spring. He also worked with Rayburn and her team to manage moisture and nutrient levels in the growing environment.

“I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that this is a huge challenge,” Lewis says. “It takes quite a lot of expertise in growing in a substrate environment versus soil. And it’s quite an expensive proposition. It’s not for the faint of heart. But we’ve proven it can be done.”

“I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that this is a huge challenge. It’s not for the faint of heart. But we’ve proven it can be done.”

– Cal Lewis

Lewis also had to be willing to share the results with other growers. NC State research is designed to be disseminated through Extension to interested growers throughout the state. As a proud alumnus of CALS and as the son of Everette Lewis, a former NC State Extension agent, he sees sharing the knowledge as almost a duty.

“I wanted to be able to prove that we could do it and show there are opportunities commercially for people to do it,” he says. “We are an extension of Extension. As leaders of the industry, I feel an obligation to share my knowledge with the smaller grower.”

All photos by Simon Gonzalez, unless otherwise noted.

- Categories: