Power of Perseverance

As NC State pursues strategic initiatives on sustainability in agriculture, the environment and education, Yates Mill’s history, downfall and restoration demonstrate the type of commitment it takes to achieve those goals.

Wood ducks paddle on the serene Yates Mill pond, giving a show to the handful of hikers on the path circling their domain. At the stone dam, the miller lifts the wooden flume’s control gate and water flows into the 32-foot-long channel. Water cascades down the enormous 12-foot water wheel until its buckets fill and it slowly begins to turn.

Inside the building an intricate series of gears, belts and pulleys come to life. As the energy builds, every timber and plank in the 270-year-old Yates Mill begins to vibrate. The mechanical din of the gristmill rises to a clamor as the millstones begin to turn and head miller William Robbins begins the demonstration of turning corn into meal.

“Everything that moves in the mill has my fingerprint on it,” Robbins says.

He’s not exaggerating. Robbins spent five years restoring the mill’s machinery and every board that was out of place with meticulous detail, retaining as much original material as possible.

Yates Mill is an elegant example of 18th century technology conceived and built out of necessity. It is the same process that ground wheat and corn in the late 1700s, when cornmeal and flour were staples in the diet. Yates Mill, and others like it, were essential tools that provided nutrition, and even some ingredients for homemade liquors, to their communities. In addition to grinding grain, other water-powered mills in the area were used to saw logs and card wool.

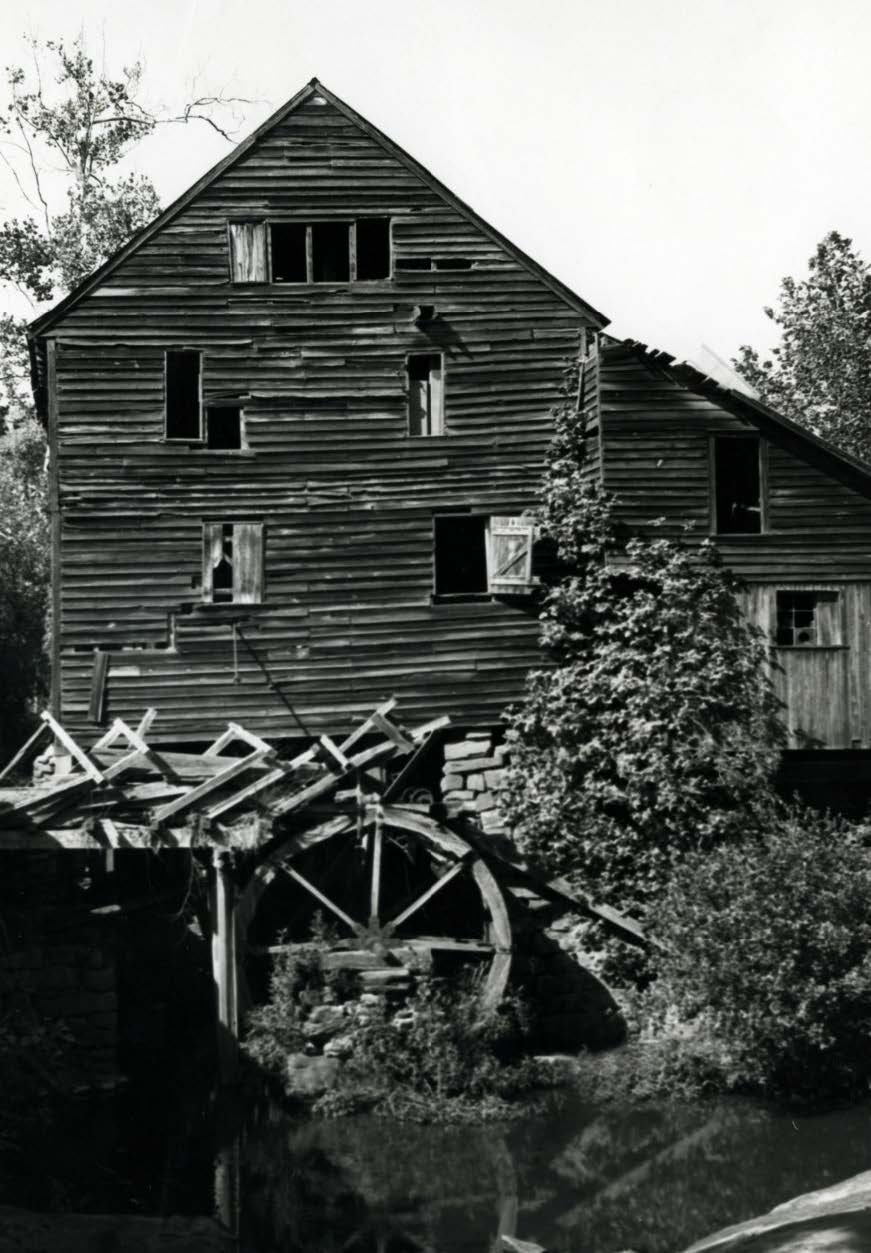

Once a center for commerce, social gathering and, of course, milling, this water-powered gristmill ceased operations in 1953 and fell into disrepair. Through the years, it withstood neglect, disuse and even hurricanes. Of the 72 water-powered mills in Wake County in the late 1800s, Yates Mill is the only one that remains.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, designated as a Raleigh Historic Property and owned by North Carolina State University, Yates Mill embodies agriculture, engineering and renewable energy. As the university pursues strategic initiatives on sustainability in agriculture, the environment and education, the mill’s history, downfall and restoration demonstrate the type of commitment it takes to achieve those goals.

NC State Gets Into Gear

Yates Mill was merely a perk of the original 1,000-acre tract of land NC State acquired in 1963 from A.E. Finley to start the Lake Wheeler Road Field Laboratory. Standing in disrepair, it served as a storage building until it piqued the interest of NC State professor of architecture Donald Barnes.

In 1968, Barnes assigned his students to build a blacksmith shop, which still stands today. They sourced reclaimed lumber from a tobacco barn in western Wake County, giving the structure an authentic historical look and feel. Today, the log cabin serves as a storage unit for the mill.

Hopefully, folks will continue to recognize Yates Mill as a standing monument to agricultural sustainability and realize that maintaining it is necessary and attainable.

In 1974, Barnes assigned 20 junior and senior design majors to create architectural drawings that could be used to restore the mill’s water wheel and the flume. The students visited Yates Mill throughout the semester, cleaning the old building a bit and cataloging the age and type of lumber used in the structure, the machines and the milling equipment. Barnes and his students created a vision for an educational site that would include a restored blacksmith’s shop and historically accurate, working gristmill.

Years later, blueprints of the mill, drawn in 1958 by two students from the College of Design, surfaced when a retiring professor cleaned out his office. Saved from his trash can, this to-scale, 13-page set of drawings would later serve as the blueprints for Yates Mill’s restoration. Those designs now live in the NC State archives.

Determined New Destiny

Over a decade later, NC State zoology professor emeritus John Vandenbergh led a class to the mill pond and noticed the declining condition of Yates Mill. In 1989, Vandenbergh joined with Chief District Court Judge Robert Rader, BA ’78 and NC State Distinguished Alumnus, and other concerned citizens in the community to found Yates Mill Associates (YMA), ultimately serving as chair of its board of directors. The nonprofit’s purpose: raise funds to restore, preserve and operate Yates Mill.

The mill restoration began in the early 1990s. YMA raised enough money to repair the building’s timber frame, install new siding and build a new waterwheel. Following nearly two decades of fundraising, YMA joined with NC State and Wake County to develop a master plan to turn the 174 acres surrounding Yates Mill Pond into a county park and nature reserve. Shortly thereafter, the group restored the mill pond’s dry-stacked stone dam—destroyed during Hurricane Fran in 1996—and then the mill itself with the help of a Federal Emergency Management Agency grant and funds raised by YMA.

When it came time to tackle the full restoration, they tapped Robbins—a local craftsman, mill enthusiast, and longtime YMA volunteer—to lead the restoration.

Head Miller, Master Carpenter and Steward

“I put my personal business on hold and I took this on as a task in 2001 and worked on it until 2006 to restore the workings of the mill,” says Robbins. The great-grandson of a miller from Columbus County, Robbins believes it’s almost fate that he became the steward of Yates Mill.

“I first saw the mill in 1969. I was a student at NC State and had an early morning job transporting milk from the research farm to the dairy plant on campus,” says Robbins. When YMA organized its restoration efforts, he volunteered, eventually serving as vice president before being contracted by the group to complete the mill’s restoration.

“I did woodwork all my life to prepare me for something like this. Early on in my career I worked for an antique dealer and reproduced furniture and repaired antiques. That’s where I developed an appreciation for how things were put together and the labor involved. Later I owned a millwork company manufacturing custom windows and doors,” Robbins says. “With antiques, they did it all by hand, and there was such detail in their workmanship.”

This was the hands-on training he would need decades later in his work restoring the mill. In the entire building, you won’t see any modern materials.

With the NC State student-drawn plans from 1958 and “The Young Millwright and Miller’s Guide” written in 1795 by inventor Oliver Evans, Robbins worked with his colleague Donnie Evans to restore the water-powered machinery in the mill. For five years, they painstakingly worked together to get the mill back in working condition. As they pieced together vintage materials salvaged from the mill, they used as many traditional tools and construction methods as they could.

“We went to great lengths to make this a museum-quality restoration,” Robbins says. “One thing powers another like dominoes. The weight of the water turns the wheel, the wheel powers the primary drive shaft, the bevel gears transfer power up to a driving bar that turns the runner stone, and so on.”

In 2006, Historic Yates Mill County Park opened to the public. Through the years the park developed miles of hiking trails, a bridge that draws fishermen and an education center—but the mill remains the park’s centerpiece and most-photographed spot.

On the third weekend from March through November, Yates Mill rattles and hums as its millstones grind corn. Onlookers watch in awe as dried corn travels down from the hopper and makes its way into the eye of the 2,000-pound millstone. There, it’s ground into fine cornmeal before exiting a spout to be collected in a bin below to later be bagged for sale. The entire apparatus is as originally designed: a historical feat of engineering that relies entirely on renewable energy from the turning of the water wheel.

The Next Turn

Robbins, now 71, remains the mill’s caretaker and head miller. Yates Mill Associates funds his position and maintenance of the mill. Often Robbins worries about who will shepherd the mill after him.

“The restoration was the main focus of Yates Mill Associates, but a long-term plan for maintenance and operation was never envisioned,” Robbins says. “How do we keep people interested in the mill? How do we keep it going and preserve it in its historically accurate condition?”

With a vibrant community of curious students and professors at NC State, there’s hope Yates Mill and its legacy will garner interest, and a new apprentice and shepherd for its future will come forward.

“We’re sitting on a very rare treasure,” Robbins says, “Hopefully, folks will continue to recognize Yates Mill as a standing monument to agricultural sustainability and realize that maintaining it is necessary and attainable.”

- Categories: