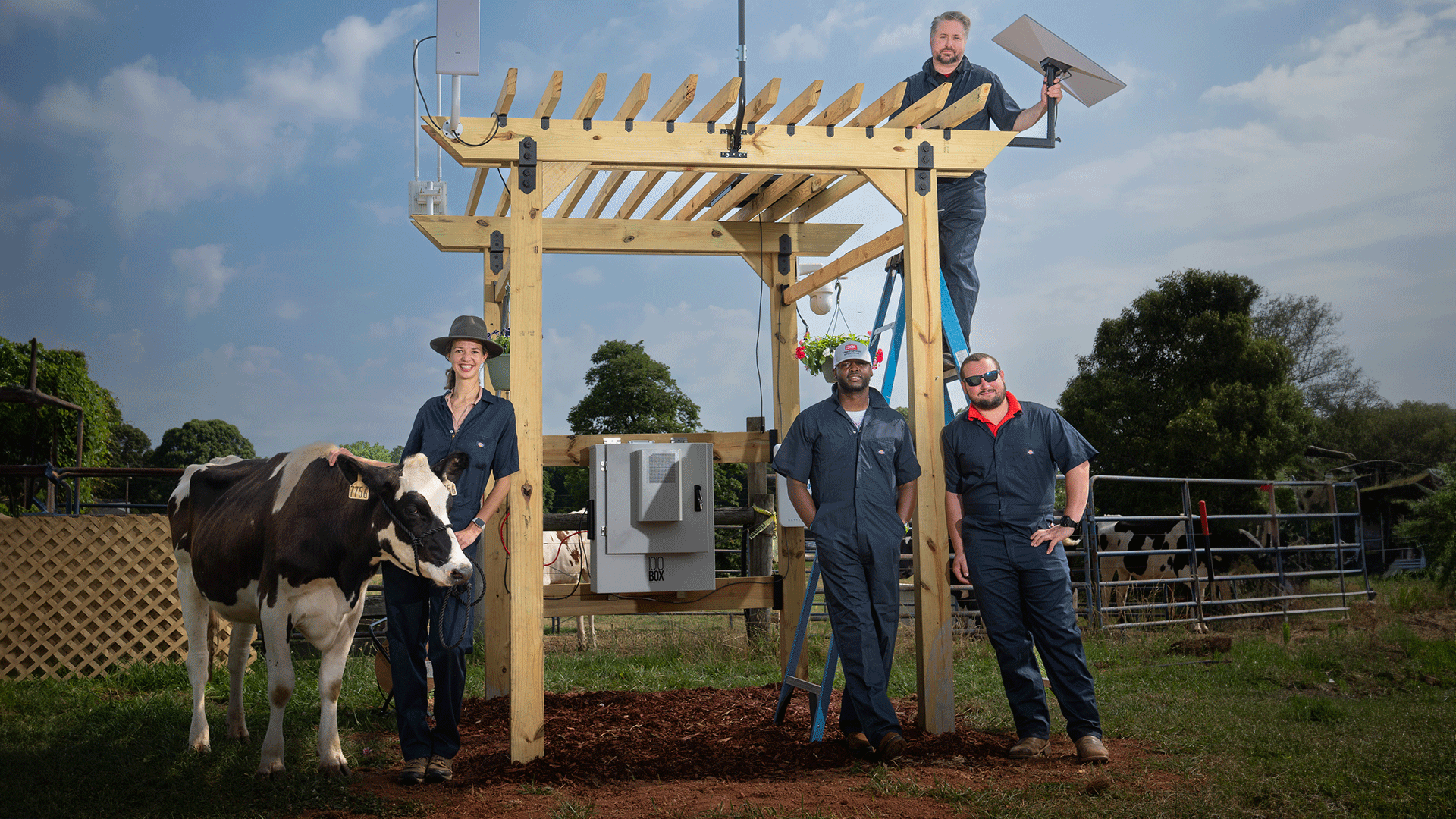

Entomologist Steve Frank can relate to undergraduates who are undecided about their career path — he was once one of them.

“I took a job in an entomology lab during my last semester in college and it sort of saved me because I had no plans,” Frank says. “Everything started to fit together. I realized I could work with plants and insects while also helping to solve problems as a scientist and professor.”

As a professor in NC State’s Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Frank now helps assess the health of trees in urban jungles.

“The reality is that a lot of trees that provide the services and biodiversity that we interact with are not in forests, but in cities.”

– Steve Frank

An active scientist, Frank has garnered more than $10 million in research funding to study why pests are pervasive in city trees, findings he shares with arborists and landscapers as an Extension agent.

“It’s easy to say that trees and biodiversity are mostly in national parks or some big protected area,” Frank says. “But, the reality is that a lot of trees that provide the services and biodiversity that we interact with are not in forests, but in cities.”

Why City Trees are Popular for Pests

A tree in the city has a tough life. On a summer day, city temperatures tend to run a few degrees warmer than in rural areas thanks to sidewalks and roads that store heat and radiate it back to the environment, known as the urban heat island effect.

But heat isn’t the only factor these city trees endure. Frank’s findings indicate heat attracts unwanted pests, too.

“What we’ve found is that temperature is the primary factor driving pest populations on these trees — and so we’ve then used that information to try and understand and predict the effects of climate change on forest trees,” he says.

Much of Frank’s work has implications close to home. He’s investigated gloomy scale insects on Raleigh’s second most popular tree: the red maple.

“Scale insects are literal bumps on a log. They don’t have legs. They don’t have eyes. They just live under a little shell and they suck juices from the plant.”

– Steve Frank

“Scale insects are literal bumps on a log,” Frank says. “They don’t have legs. They don’t have eyes. They just live under a little shell and they suck juices from the plant.”

Using satellite images and data loggers, Frank has compared red maple trees just a few blocks away from one another that differ by a few degrees in temperature. He discovered that an increase of just 2 degrees in temperature increases the gloomy scale population by 300 times.

“They cover the entire bark of the tree and they’re sucking on the resources that the tree needs to grow and survive,” Frank says.

Scaling Up Scientific Findings

Frank’s findings have long-term implications for climate change: city trees give scientists a glimpse into how future warmer temperatures could affect forests. At the same time, Frank has used his findings to make recommendations that can prevent unnecessary tree deaths now.

“We’ve developed thresholds where if there’s a certain amount of impervious surface around a site where you want to plant a tree — if it exceeds 30% — then you shouldn’t plant the red maple because it will be too hot and dry,” Frank says.

After hearing his guidelines, the City of Raleigh reduced its planting of red maples and diversified to other tree species.

After hearing his guidelines, the City of Raleigh reduced its planting of red maples and diversified to other tree species. Frank enjoys working closely with arborists and landscapers across the state to make a difference.

“They’re super jazzed to find anything that will help them maximize the number of trees they plant and the number that survive with the least maintenance,” he says.

It’s this collaboration and creative problem-solving that initially drew Frank to academia.

As a mentor, Frank often helps solve problems of a different kind — whether helping new faculty navigate unexpected aspects of their job or graduate students become independent scientists. He especially relishes the opportunity to foster undergraduates’ courage to solve problems.

“You have got to just try it,” Frank says. “You’re going to fail sometimes — a lot of times — and that’s okay. You try to tackle things as best you can.”

All photos by Marc Hall, unless otherwise noted.

Graphics by Patty Mercer.

- Categories: