Future-proof Farming Starts with Fiber

A group of dedicated people across the state are bringing high-speed internet and advanced AI technology to our research stations and field labs in a collaborative effort to move our food system into the future.

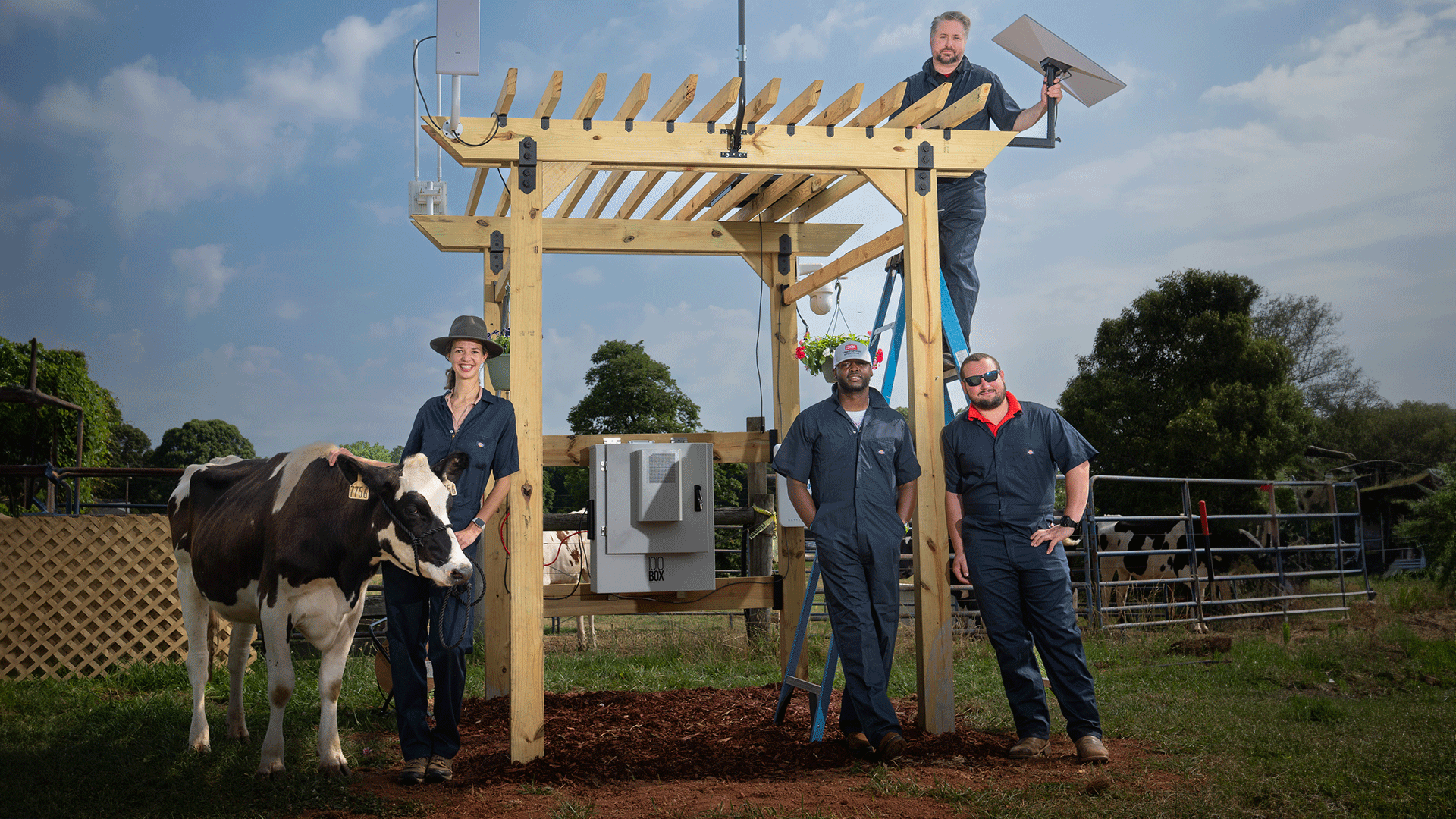

‘Twas a week before Christmas, when all across the state, not a creature was stirring … except the CALS Research Computing Team at NC State University. Armed with tractors, excavators and spools of fiber optic cable, Jevon Smith, Brendan Riddle and Trevor Quick spent a chilly weekend in December of 2023 building fiber optic pathways to bring high-speed internet to the Horticultural Crops Research Station in Castle Hayne, North Carolina.

“The technology we’re installing isn’t commonly found on farms, it is much more likely to be seen in a Google data center,” Smith says. “Our work has novel applications in many ways — it’s very experimental for all of us.”

The goal of the Research Computing Team: lay critical tech infrastructure necessary to future-proof farming in North Carolina.

A Look Back on Moving Forward

Had Smith, Riddle and Quick stopped to contemplate how they came to be installing fiber at a research farm on a weekend before Christmas, they may have had to think back to the 1800s.

Agricultural research has been conducted for nearly 150 years in North Carolina at what were once called Experiment Stations. Today, NC State, in partnership with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (NCDA&CS), runs the second-largest research station network in the country, with 18 stations and four field laboratories that range in size from 101 acres to several thousand, each representing unique climate and soil conditions.

Most of NC State’s plant breeding research happens at research stations. As “living laboratories,” the stations enable researchers to investigate crops, forestry and environmental concerns, livestock, poultry, aquaculture and even weather patterns.

Over the lifetime of North Carolina’s research stations, advancements to equipment and technology have revolutionized how food gets to our tables and how rural communities operate.

North Carolina has the ninth-highest percentage of residents with inadequate broadband, totaling nearly 1.3 million people.

Without access to broadband internet, that work is at risk of falling behind.

In 2022, the federal government allocated more than $42 billion to the Broadband Access, Equity and Deployment (BEAD) Program to build infrastructure and increase broadband adoption equitably nationwide.

The program prioritizes unserved communities (defined as receiving less than 25 Mbps) and underserved communities (defined as receiving 25 to 100 Mbps).

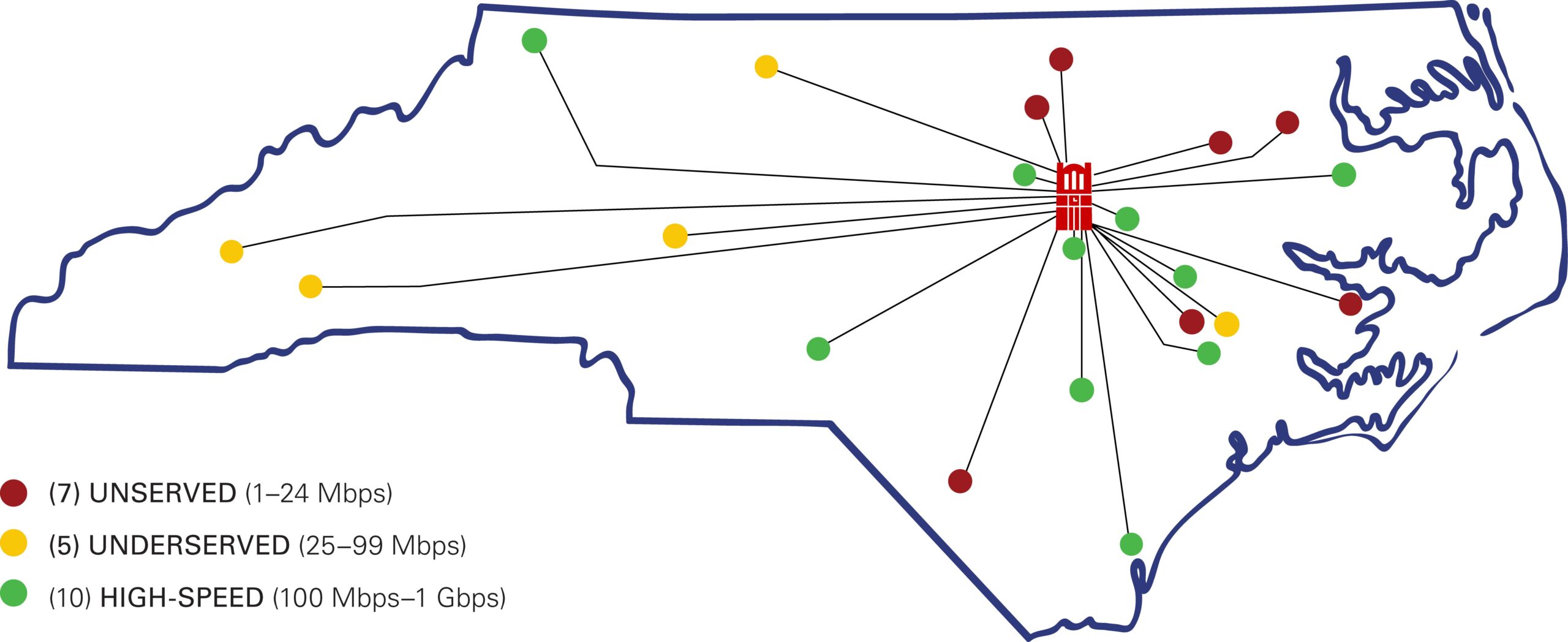

An estimated 22 million Americans live in unserved communities. North Carolina has the ninth-highest percentage of unserved residents, totaling nearly 1.3 million people, according to new BroadbandNow data. In terms of NC State’s research stations, 12 out of the 22 research stations and field labs are underserved or unserved.

Because research depends on good data, and good data today relies on internet connectivity, broadband allows researchers to deliver the most high-impact, relevant recommendations across the state. Luckily, a dedicated group of people at NC State is bringing our research stations into the modern era, one line of fiber optic cable at a time.

“Massive data collection and analysis are now required at the field level to provide the next generation [with] decision-making tools, predictions and variety development,” says Steve Lommel, director of the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service and associate dean for research in CALS. “That’s why fast fiber is needed at every station.”

The Fiber Project

To bring broadband to North Carolina’s research stations and field labs, a motivated group of collaborative individuals across NC State and NCDA&CS has been working toward a common goal: Get every research station and field lab connected to high-speed internet. Nearly half of the research stations have at least 100 Mbps of broadband speed, but the ultimate goal is to get every station up to 1 Gbps to align with the highest standard.

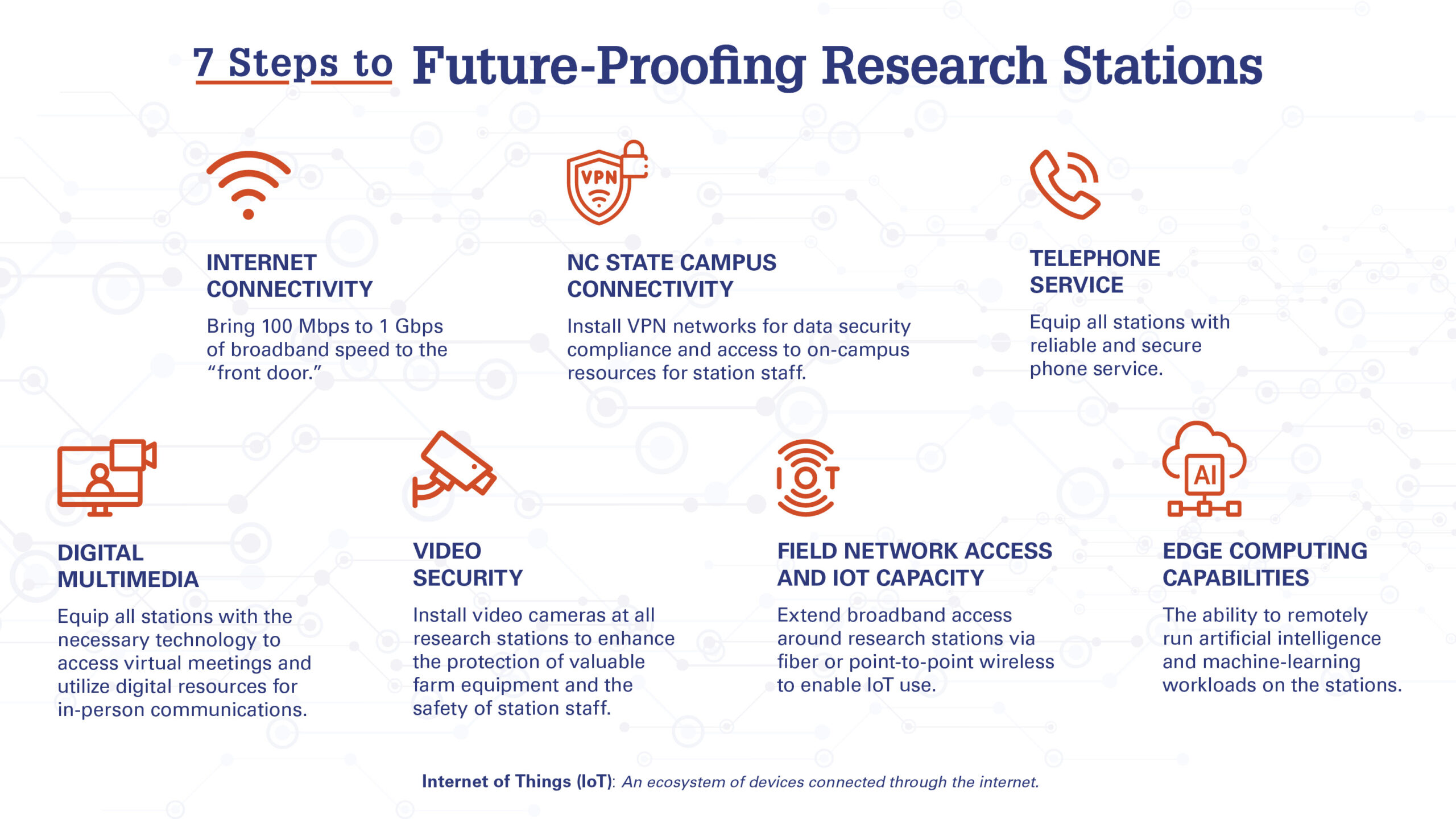

But the fiber project doesn’t just stop at high-speed internet, which will bring fiber optic cables to the “front door” of every station. That’s just phase one of a seven-step process.

“Nothing else can happen without the initial connection to the internet. But once it does, everything becomes possible,” Smith says.

“We don’t just need this on one station, we need it across our entire system so that we can work on projects from the mountains to the coast and serve all our clientele,” says Loren Fisher, director of research stations and field labs at NC State.

“We don’t just need this on one station, we need it across our entire system so that we can work on projects from the mountains to the coast and serve all our clientele.”

– Loren Fisher

And a digitized research station network won’t just meet today’s demands; it will position the state’s researchers to meet the demands of the future. The dynamic nature of both technology and research necessitates flexibility. Smith and his team are building project- and tech-agnostic systems so the stations can accommodate anything a faculty member might need or a farmer might ask about.

“Our stations can be a testbed for technologies that benefit growers just like any other management practice NC State faculty study at the stations,” says John Garner, superintendent of the Horticultural Crops Research Station in Castle Hayne. “It’s about providing value to the agricultural industry in our state.”

It’s also about being able to meet biosecurity and chemical security regulations and expanding the ability of NC State faculty to pursue new research funding through improved access to data security. Ultimately, though, it’s about feeding people.

“If we are going to continue to feed a growing population, with fewer resources like land, water and labor, those of us working in agriculture must improve our efficiency. Technology and research are the only ways to achieve that goal,” says Teresa Lambert, director of the Research Station Division for NCDA&CS.

Fiber to the Front Door

To help prepare North Carolina for the future of agricultural research, NC State and NCDA&CS have partnered with MCNC, a nonprofit organization that owns and operates one of America’s longest-running regional research and education broadband infrastructure networks. North Carolina’s education, research, library, healthcare, public safety and other public institutions are all connected on the same network through MCNC.

Smith explains that the Research Triangle didn’t become what it is today by accident. The ability of Duke University and UNC-Chapel Hill to develop world-renowned cancer research was in part made possible by being connected to a secure network, established by MCNC, through which they could share information.

“We’re doing the same thing for agricultural research,” Smith says.

MCNC conducted an engineering review of every research station to assess the feasibility and cost of bringing in fiber. The Central Crops Research Station near Clayton, for example, was on dial-up internet until 2018, when MCNC connected the main administrative building to fiber.

Now, Central Crops is one of the most advanced research stations in the system as one of only three with any IoT capacity or a campus VPN connection. High-speed broadband at the station makes it possible for faculty across disciplines to conduct advanced crop stress research, breed more resilient plant varieties, and monitor major agricultural pests, all with better, more accurate data.

IoT in Action

People have been researching the use of drones in agriculture for over a decade.

“A lot of the basic things that we have to quantify can be done so much faster from a drone,” says Chris Reberg-Horton, a professor in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences and the director of resilient agricultural systems for the N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative.

Plant breeders can use data collected from drones to quantify the traits they are breeding for, such as drought tolerance or growth rate, and identify, diagnose and treat stressed plants. But Reberg-Horton emphasizes that anyone doing digital ag research can only work at stations with internet connectivity. He says that some crops and regions are being left out as a result.

Jeremy Martin, superintendent of the Sandhills Research Station in Jackson Springs, explains that the Drone Pilot Project started at his station not only because it’s one of a few with high-speed internet connectivity, but also because of the area’s sandy soils, which are ideal for intentionally stressing plants through nutrient and water limitations.

The N.C. PSI Compute Team leading the Drone Pilot Project aims to develop a synergistic, accessible system of drone data collection and analysis that any researcher can use. The idea is for research station staff to conduct weekly drone flights of every research plot at the station, collecting every primary type of data used in plant trials. Field researchers have agreed on a standard set of sensors for drone flights that includes camera imaging and multispectral imaging calibrated to the light plants respond to.

After a day’s flight, the station staff member loads the data on a computer at the station into an app that Reberg-Horton’s team has developed. At midnight, the data migrates back to campus to be processed and stored.

“The high-speed connection that we have at Sandhills is what allows that midnight data transfer to take place. If they didn’t have a broadband connection, you could forget it,” Reberg-Horton says.

After a successful transfer, a second app developed by the N.C. PSI Compute Team stitches as many as 20,000 images from the previous day’s flight together into one large image of the entire station. The app then calculates indices of interest that get stored in a database for access at any time. The intention, Reberg-Horton says, is to eventually have an archive of every research station every week during the growing season in the hopes of answering both anticipated and unanticipated research questions.

“Drones are just the tip of the iceberg. We plan to move into data collection via ground-based robots and tractor-based imaging systems for other crops.”

– Chris Reberg-Horton

“Drones are just the tip of the iceberg,” Reberg-Horton says. “Not everything can be captured from the skies. Fruit crops with thick canopies, for example, need to be imaged from the sides and below. We plan to move into data collection via ground-based robots and tractor-based imaging systems for other crops.”

The Future of Farming

Beyond drones and robots, the data those devices collect must ultimately add value for the end user. With the future in mind, Smith has left room for evolution. Eventually, the cabinets that house the internet equipment on every research station will also play host to machine-learning hardware.

“It’s not only about data collection for our researchers,” Fisher says. “It’s also about testing new technology that farmers can employ on their farms. And they’re already asking us questions that we aren’t ready to answer and won’t be able to answer until we have high-speed internet capabilities on our stations.”

The kinds of questions growers are asking relate to the financial pros and cons of adopting new technology. Will a drone save them money on labor, chemicals and equipment? Is it as effective at managing pests and disease? Or, they may have already adopted data-generating technologies but aren’t sure how to best utilize the information or apply it to management decisions. The power of a digitized research station network is in quantifying the value of technological investments that can push North Carolina farmers into a league of their own in the global marketplace.

“AI and digital ag is the revolution of our time.”

– Chris Reberg-Horton

“AI and digital ag is the revolution of our time,” Reberg-Horton says. “It’s about NC State staying on the forefront of innovation.”

All graphics by Patty Mercer.

- Categories: